THE BODY IN REVOLT

About the making and directing of "As long as the world needs a warrior’s soul"

an essay by Hendrik Tratsaert

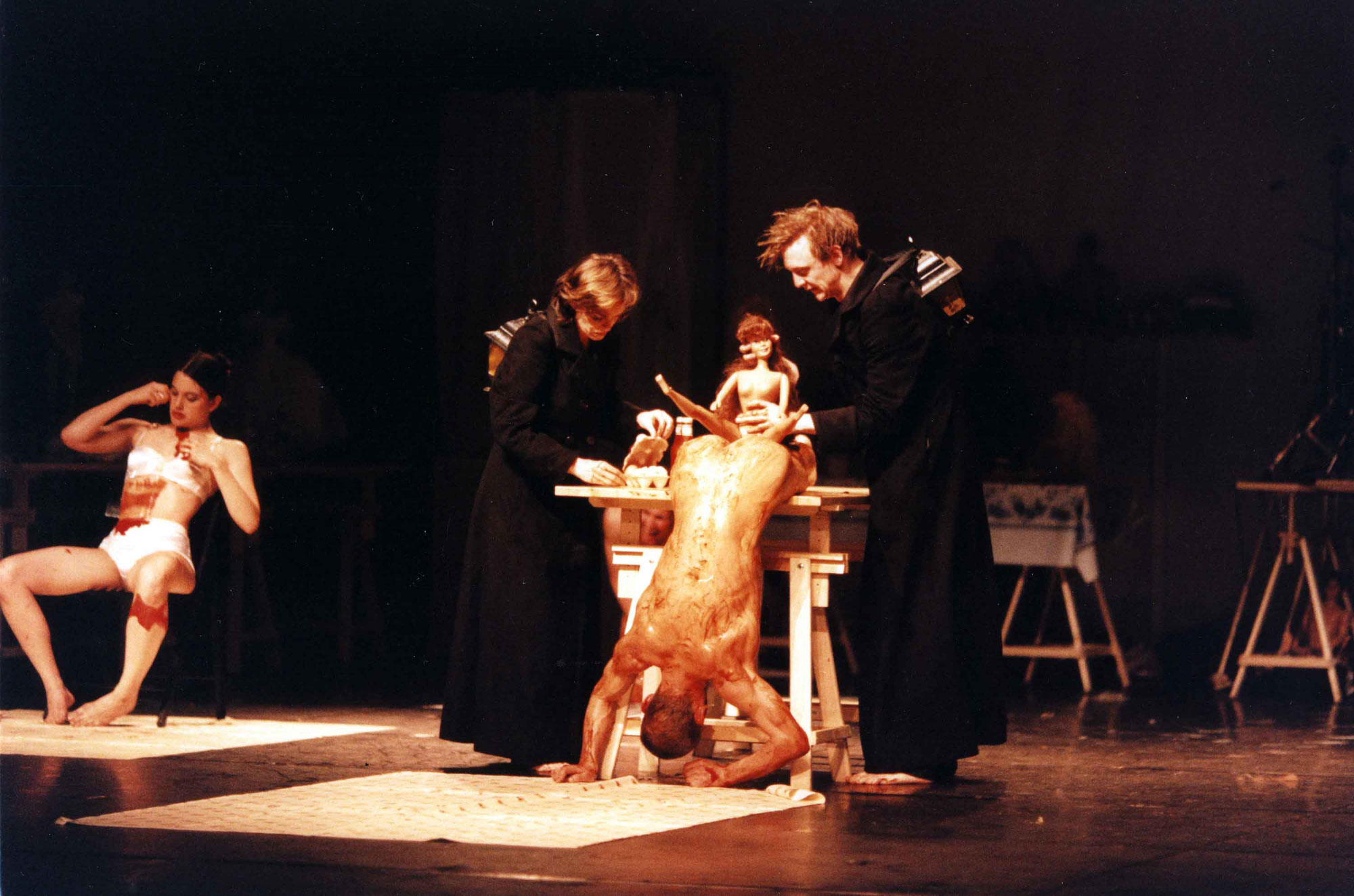

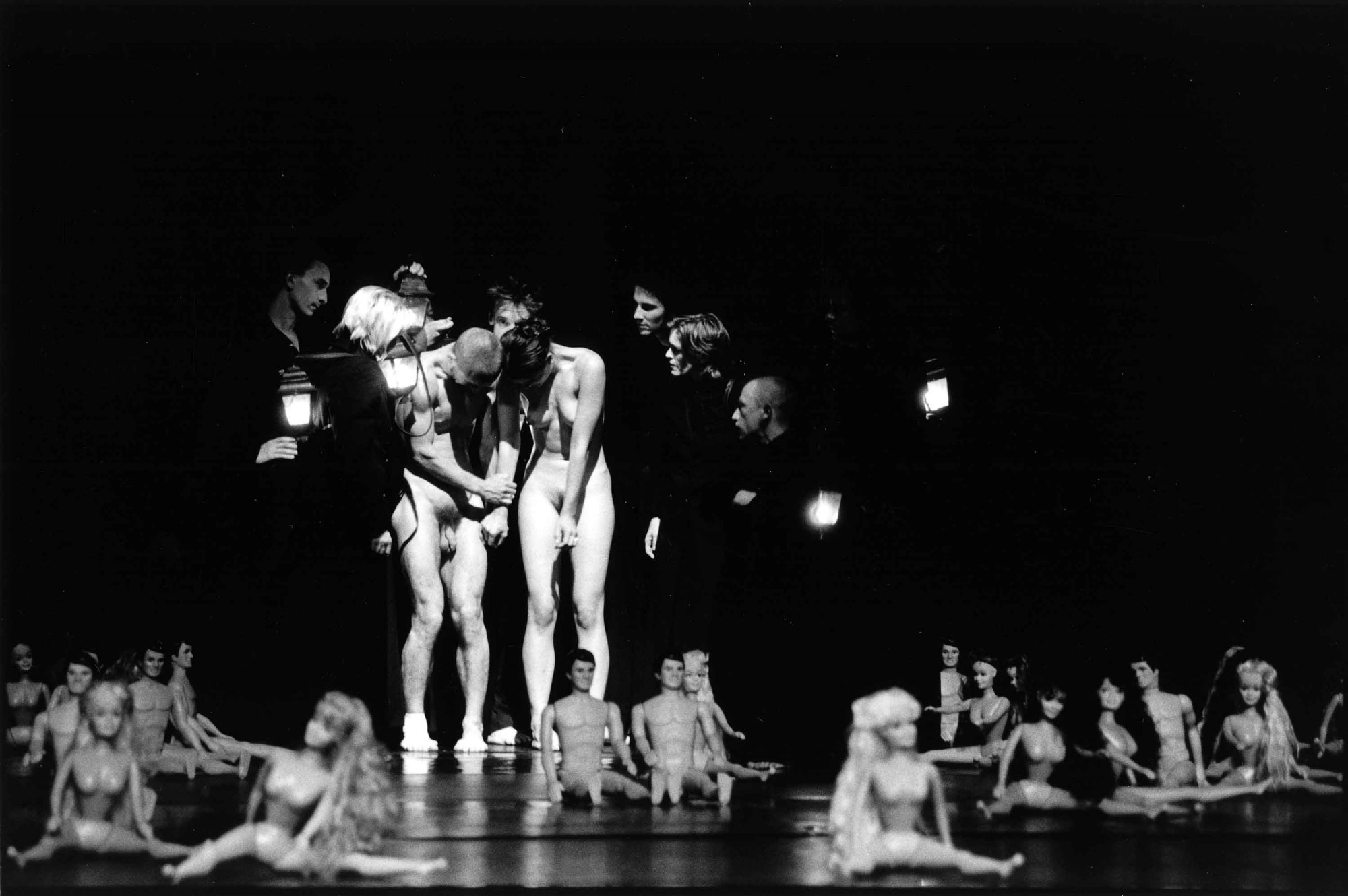

Jan Fabre’s theatre performance As long as the world needs a warrior’s soul (2000) opens with a naked man and woman in the middle of a dimly lit ‘space’ that is littered with dolls. They are being herded together by a group of people who ask them in a commanding tone of voice, ‘Did you do it?’ with an emphasis on ‘it’. If their answer is affirmative, the response is laconic: ‘No big deal’. Paradise lost? Paradise regained?

This production came into being by way of a process. The central theme of ‘body in revolt’, only acquired form and meaning within the working process. Jan Fabre deliberately worked with a completely new group of actors, dancers and musicians, with the exception of Els Deceukelier, who is a long-standing member of the company, actor Jurgen Verheyen and dancer Erna Omarsdottir.

Dancer Lisbeth Gruwez talks about the early rehearsals: The general tone developed during a two-week workshop that preceded the proper rehearsals. The group drawn from auditions was initially larger. And in this workshop atmosphere we started to work at a very high tempo: inventing various characters, performing a range of tasks, accumulating material, looking for sources, etc. Jan Fabre encouraged the group to give a very energetic performance, in which the notion of resistance or protest played the most important part. The only concrete element that was present right from the start was that of the dolls. You had to integrate your doll – every actor, dancer and musician had their own doll – into every new assignment, and also involve the element of ‘protest’ in it by uttering three sentences expressing a mild form of protest against a certain situation, while involving your doll. Another improvisation assignment was called, ‘To teach a puppet: an impossible thing’. You invented a character that was teaching a doll to swim, to walk, sleep or grow. Most important was that you never gave up and that you believed that if you explained things properly, your mission would succeed.’

The image of doll versus the human body is an underlying feature of the performance. This metaphor is developed into an allegory. Seen from the viewpoint of the characters or bodies in action, this works in two directions. They cherish a desire to become a doll themselves, which enables them to free themselves of the burdens of the body and its functions. In this way wishes and desires are projected onto the doll. The counter movement is a resistance to the doll, against making the body submissive and servile. The body expresses its individuality by opposing a process of dehumanisation.

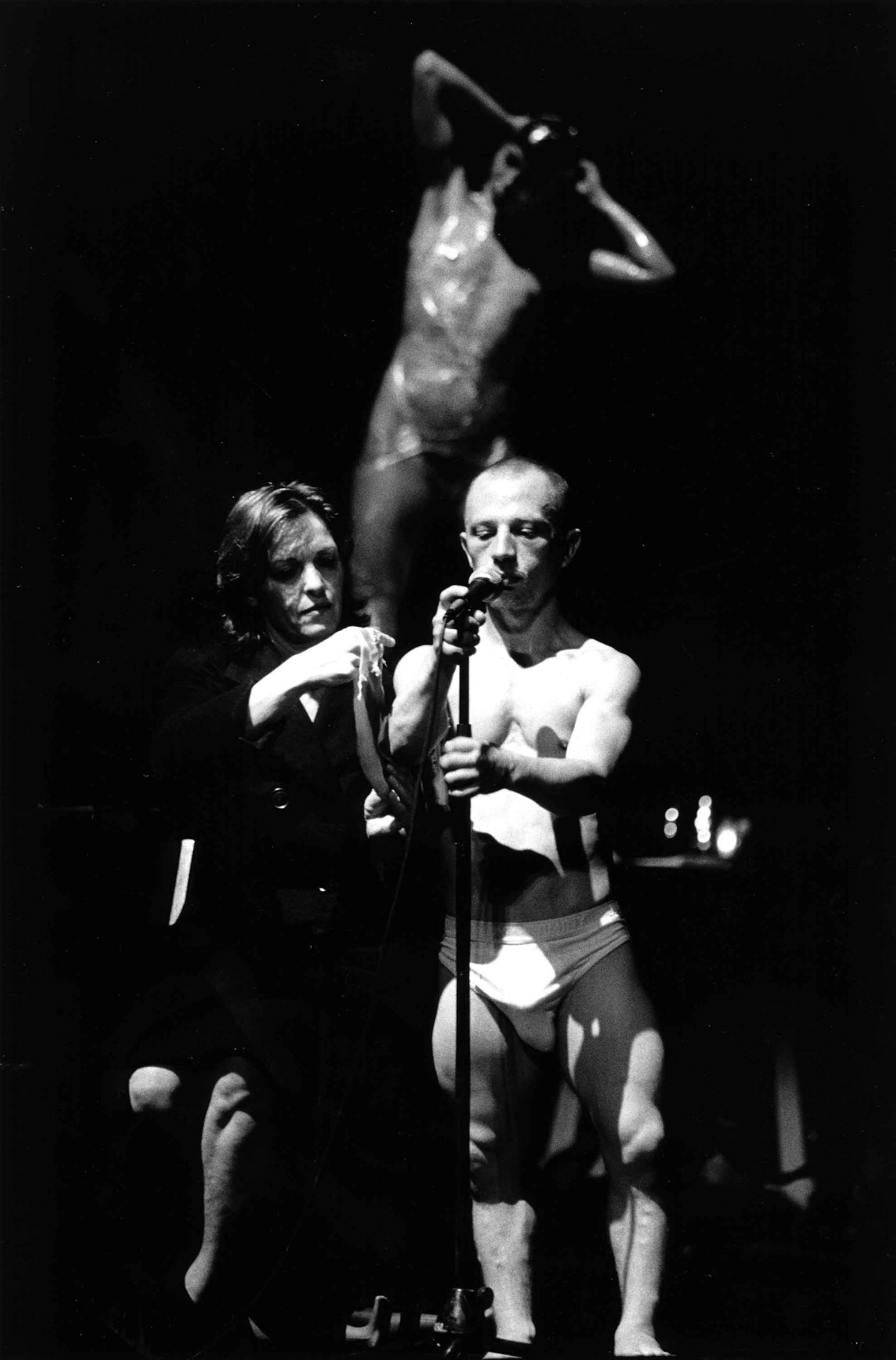

LOUD AND CLEAR

The language of the performance is very direct and instinctive. It is like chemistry, with action and reaction. This is why ‘As long as’ uses the striking power and the confrontation of rock, which has a liberating effect because of the energy that this genre of music is able to generate. In developing the textual drama of the performance, Jan Fabre and the group selected texts that had the directness of rock: succinct, clear and to the point, unavoidable and ‘in the face’. It is impossible not to have an opinion or to hold halfhearted views. The series consists of the monologue Io, Ulrike, grido (Moi, Ulrike, je crie) by Dario Fo, the jazz standard Strange Fruit, and the songs Le Chien by Léo Ferré, Sabotage by John Cale, and Killing in the Name of by Rage Against the Machine. It is ‘the stuff of resistance’, a product of the times, with a hard core.

Dario Fo wrote Io, Ulrike, grido in the seventies, basing it on journalists’ diaries and the German member of the RAF, Ulrike Meinhof. She died in prison under unexplained circumstances at the age of 41.

Actress Anny Czupper talks about the choice of texts: “Initially Jan Fabre asked me to look for pornographic literature and texts on the warrior. The texts that emerged and appeared on stage didn’t really work in the range of usable improvisations that had developed, or with regard to the tone of the performance. It came across as being rather contrived. There were also other combinations of texts and characters that didn’t work either. It made it look too much like a collage. We were looking for something with more grit, and very direct. The text of Ik, Ulrike, schreeuw het uit by Dario Fo worked very well. We discovered a parallel between the description of the hyper-structured aseptic hell of the prison and the hysteria on the stage. A shock of confrontation between word and image. We were less interested in the anecdote in the text about the female German terrorist who languishes in prison, than in the discourse on the tyranny of hygiene and the revolt and commitment during her life and imprisonment.”

The script of Io, Ulrike, grido bears traces of the period in which it was conceived: virulent feminism and the occasional use of Marxist terminology to describe western capitalism. The play is simple and is no more than a document. The female figure coolly registers how all the vital functions fade, become perfunctory, clean or even absent. It is a clear account of the alienation of the body and therefore of society, while this very same society has devised a machine that causes this alienation.

The songs in the performance are not only used for their rhythm and melody, but very deliberately for their content, which contributes to the intensity of the performance.

Strange Fruit (1940) become known through Billie Holliday’s version. Sung softly, it was a bitter protest against the lynchings during the period of apartheid imposed on black Americans. The ‘white niggers’ of the performance and the cycle of ‘births’ place the song in a different perspective. In 1969 the French cabaret singer Léo Ferré released the album ‘Amour et anarchie’, which included the parlando song, Le Chien. It is an ode to love as an act of subversion, and advocates a poetic resistance to the established order: Nous sommes des chiens de bonne volonté…Je cause et je gueule comme un chien. JE SUIS UN CHIEN. The song is played live. It emphasises the isolated image of a dancer-actress who manically repeats a movement halfway between spasm and stylisation while holding a lump of butter in her mouth. Lisbeth Gruwez says, “We improvised on the theme of lust. I tried to come as a man in a woman’s body. It was supposed to be an incantation, a ritual. During that solo moment I suffer and I fight back. Like a flower that wants to grow in my belly, despite all the mud. Someone who is hurt can become a warrior.”

At the height of the punk era, John Cale, the singer-songwriter and ex-member of Velvet Underground, released the obscure record, Sabotage Live (1979). The group of musician-actors here play an improvised, a-rythmic live version of it. The text is brutal and an evocation of the need to oppose the banality of everyday life with an act. Sabotage forms a break that contrasts with the orchestrated chaos of the performance. It is a song that constantly sabotages its own structure.

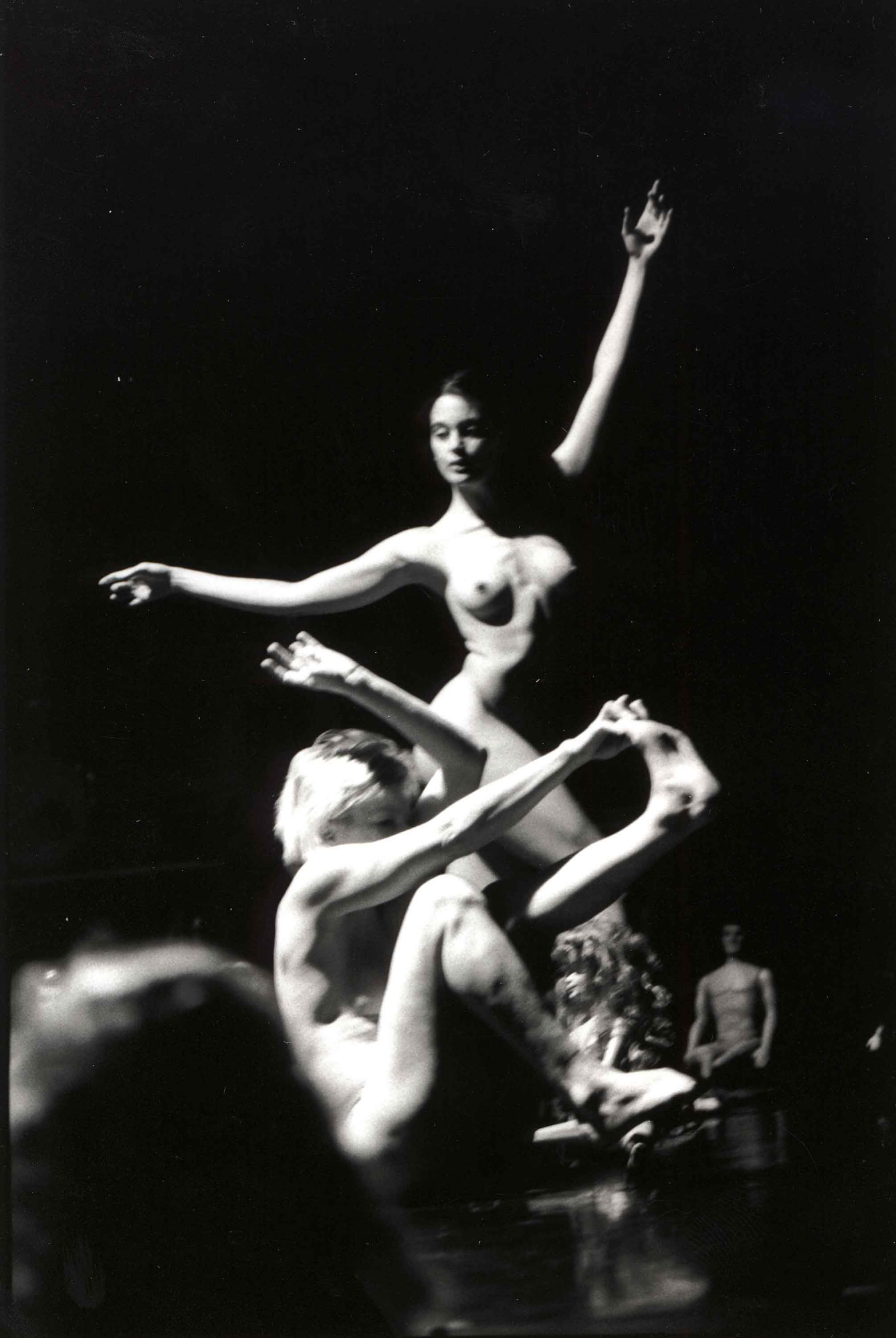

Killing in the name of is the main song on the hit album made by Rage Against the Machine in the early nineties, and was born in the underground scene of the Los Angeles metropolis. In the evolution of the series of ‘resistance’ songs in the course of time, this song is lacks any of the romance of the struggle. ‘Those who died are justified for wearing the badges. They are the chosen white. Fuck you. I won’t do what you tell me.’ The song testifies to a blind hatred of the system and of overt racism. The dance sections that accompany this raw rock are the stylised culmination in movement of essential images in the production.

According to the dancer Liesbeth Gruwez: “For the dance set to Killing In the Name of, when the floor is completely soiled, Jan Fabre wanted to link classical ballet steps to impossible movements, to things a doll cannot do. One of the things he confided to me was that for the arrangement of the stage space as it ultimately appeared, he had been inspired by Pier and Ocean, the painting with the horizontal and vertical areas of colour by Piet Mondriaan. He wanted a main group movement extending from front to back, as if in battle formation, like a Greek phalanx on the march, and not just a chance military formation. From this we drew a-rhythmic solo improvisations that disrupted this solid image and were then reintroduced back into it. I call it a military dance: there is a huge amount of drive behind it and it is technically brilliant. Because the floor is absolutely filthy, you appear to be dancing on an open sewer and you struggle to maintain your balance and your position. He said to the dancers and the musicians who were also giving it everything they had, “The finale must be like a door that flies off its hinges. The hinges begin to shake and then snap.” Here you cannot dance and quietly think about what you are supposed to do and then simply resume your position. You get up and react.”

TO THE SEEFHOEK AND BACK

In As long as the world needs a warrior’s soul the symbols are in parallel and superimposed: text and songs, familiar characters alongside actions that start to resemble rituals, the image of the doll and the derivatives. The juxtaposition of symbols invites a certain type of viewing: not taking one of the symbols as a guideline, such as the monologue in several parts, but defining and bringing together different lines, as a whole, in contrast to a classic, logical structure.

The actress Anny Czupper talks about the directing: “Fabre builds up a huge amount of energy onstage, and is able to motivate people individually as well as in a group. On the one hand, he is someone who knows what he wants, but during the work process he is constantly open to new avenues and to suggestions made by actors and dancers. Consequently he continually stimulates, kneads, tears off, and is prepared at any time to ditch everything or transform it on the basis of new material that is handed to him. This comes from an intense interest in others and things that are different. An actor spends every second giving his all to what he is doing. That is what is expected of you here, no more, no less. His ‘here and now’ attitude, which allows for chaos and adventure, is confusing but also enriching, for actors naturally want security: they are involved in a constant battle with their own fears.”

The spoken and sung material in this production together form a whole which, although from different periods, all have the same core. Of course together the songs and the Meinhof text form a statement and are all determined by the periods from which they originate. They are advanced and cherished as documents from the twentieth century now passed, as ‘signs of the time’.

Jan Fabre explains: “This is the most political production I have ever made. It evolved organically. We set to work with a young group, who for example gave their own committed interpretation to ‘the warrior’ through the music they introduced. I asked them to bring along material they saw as being spiritually related to a contemporary warrior. This gave rise to the thread running through the collection of committed songs covering different periods, and by way of Dario Fo’s text.

However, the deciding factor was working in the Seefhoek, which was a new experience for us. I realised that despite the popular character of the area, it was very racist, and there are many people with extreme right-wing beliefs. Quite unintentionally this production has turned into a political statement in a form that is not based on positive or negative identification (the goodies and the baddies), but on confrontation. I find that too much theatre expresses a liberal-social behaviour which although honest and responsible, is nevertheless also very smug. I call this type of theatre ‘design’. It doesn’t form a distraction, it fits in everywhere and it is completely harmless. It is not my cup of tea.

REVOLT AND IMITATION OF THE BODY

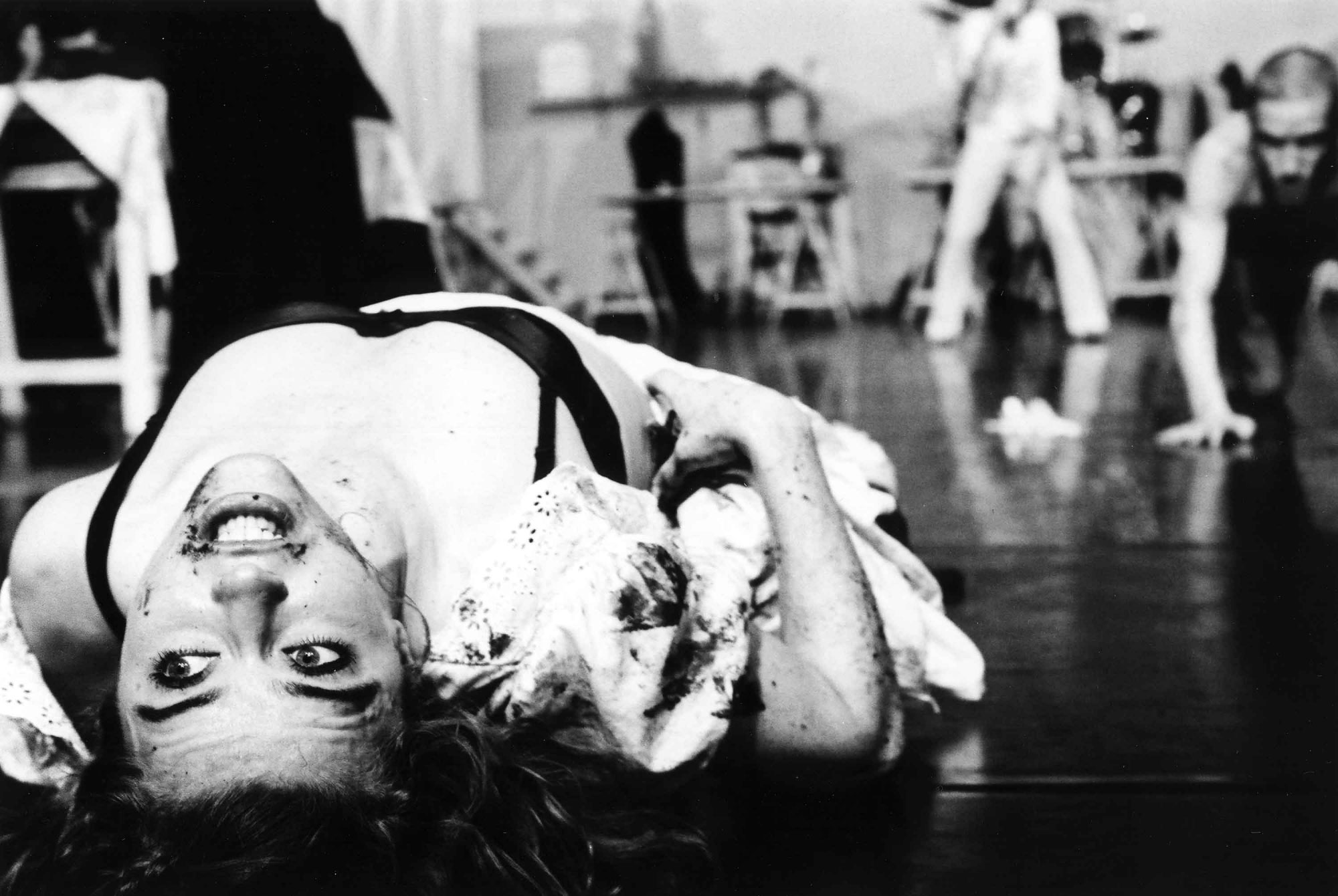

The extremely physical and alienating actions before, during and after the text initiate a dialogue with Meinhof’s words. The aseptic world they describe – colourless, odourless, and stripped bare – is counterbalanced by an extreme physicality and a sequence of actions. The actors encounter one another in an artificial laboratory.

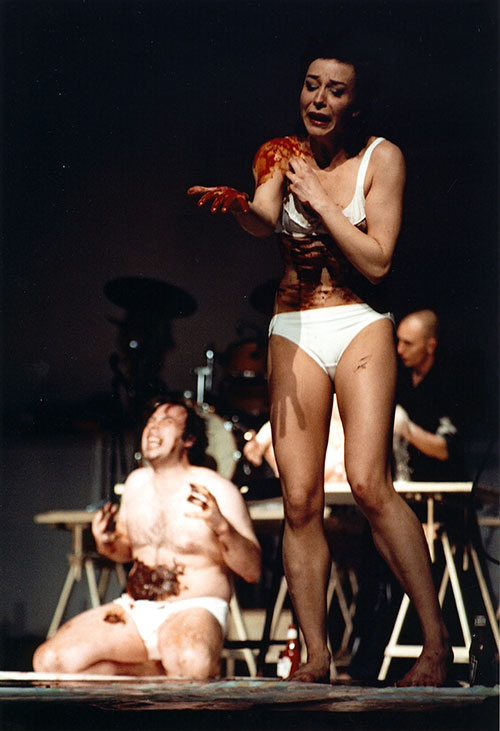

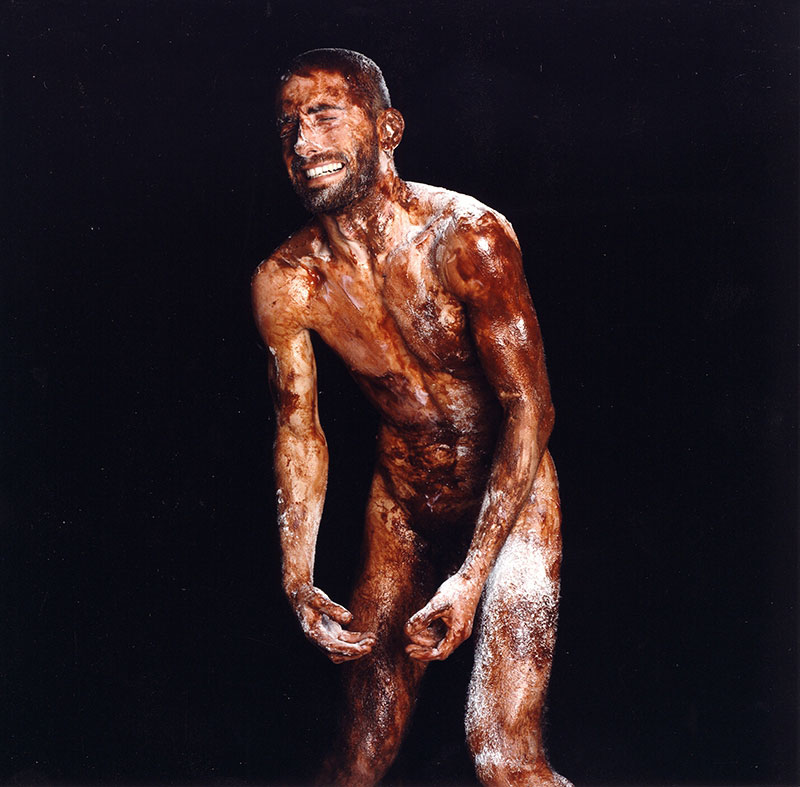

Lisbeth Gruwez talks about this aspect during rehearsals: “During the weeks before composition you were motivated into thinking about the human-doll relationship: what do I like?, what not?, what are the differences? I thought: a doll always has a perfect skin, a doll never dirties itself, a doll cannot menstruate. We have liquid, bodily juices, bodily functions. And then we started working with substitute materials: ketchup, chocolate and eggs. The (obvious) conclusion that man feels desire was a determining factor in many of the improvisations: the desire for eating, for sex, for work, the desire for destruction, death. One of the improvisation assignments was called ‘Whatever is acquired with difficulty is desired with lust’.”

The aseptic world of prison (extrapolated to society) described here wrestles with the substitute bodily matter the actors use to create an identity for themselves. There is a shift in meaning: ketchup becomes (imitation) blood, chocolate becomes a second skin and resembles faeces. Flour and eggs are used as something to play with or as decoration. Broken eggs become skin infections. Flour is used for adornment in the way that a tribal warrior covers his skin. This ‘food’ is therefore used to strengthen both the inner and the outer body. This phenomenon provides a charged semiotic field of varying direct meanings, associations and functions.

The actors, for one can hardly call them characters, act as if they were the living components of an installation, in a manner that is as direct and provocative as an art performance. The ritual cruelty Antonin Artaud saw as the future of Western theatre, beckons.

The arrangement of the space into an elongated U-shaped workbench ‘personifies’ the ritual of preparing food, smearing nutrients onto the body, and removing them. The actors take pleasure in this. They develop an anthropology of eating, and focus a considerable amount of their attention on bodily functions and organs. The cleansing of the body – they shower one by one – concludes the ritual.

In Jan Fabre’s latest production, the body is more present and even more ecstatic than ever. It is in revolt. It exhausts itself; it is vibrant. It is manipulated, besmirched and besieged. As if it wills itself only to be natural and wants to personify the septic, including infections and chaos.

Following the Fabre trilogy of the body, comprising the spiritual (Sweet Temptations), the physical (Universal Copyrights), and the erotic body (Glowing Icons), we speak of the body in revolt. This specific appearance of the body contains elements of what one could call the ‘cold’ body: a body that becomes purely instrumental, as in a pornographic commercial. Or cold in the sense of pure (dead) materiality that is laid out and is no more than meat. The attempt to double with the doll links up with the idea of the substitute body, which has frequently been, and still is, a subject explored in art by artists such as Duchamp, de Chirico, Schlemmer, Bellmer, and Cindy Sherman. Or else the field of art is abandoned for science and technology to specific applications in the field of genetics (cloning) and in new media (cyber-people, virtual bodies).

THE SMALL WARRIOR

As long as the world needs a warrior’s soul does not refer to historical myths or more contemporary examples, and the romanticism that goes with it. There is no classical hero or person with exceptional qualities. It is the small, everyday warrior who is most important. The small warrior commits an act of resistance that is spontaneous and individually determined. He does not perform great, stirring deeds. He determines his place in reality using the only direct instrument at his disposal: his body.

The actions of the warriors are primary in their intensity, and their impulses lie close to nature. It is no coincidence that the act of giving birth is portrayed several times, with the accompanying simulation of the battle and the pain of birth that goes with it.

Actress Els Deceukelier: “In the performance the female, and in particular the mother, is more important than the warrior. There is something animal that emerges in the actual confinement and the pain that the woman has to endure. New life demands an intense concentration of energy, I think. A person who comes out of another person, and the body that is almost torn open for that purpose, is a moment when the woman loses everything, and civilisation is replaced by pure instinct. The female has more primitive instinct. She is closer to nature, and is therefore more of a warrior.”

The small, everyday warrior is an instinctive warrior. As such, he or she is more an individual of ‘the one-man move’ than of a revolution. The motto of the writer and humanist Albert Camus ‘Je me révolte, donc nous sommes’ in L’homme révolté should therefore be changed, as the writer did in L’été, to ‘Je me révolte, donc je suis’, to the singular.

Here he or she is not part of a broad social movement. Is this warrior a warrior of defeat? Is the energy that is released, the battle itself, sufficient?

The work is the result of discontent and a distaste for cynicism, even if there is no chance of evolution. The nucleus of As the world needs a warrior’s soul is not so much commitment (in the social sense of the word), as his body in revolt, in everyday resistance. In any case, surrender is not an option.

Direction, scenography & choreography Jan Fabre Dramaturgy and artistic assistance Miet Martens

Performers - creation: Cédric Charron, Anny Czupper, Els Deceukelier, Frans-Jozef Goof, Lisbeth Gruwez, Saskia Hoffmann, Erna Omarsdottir, Frank Pay, Diederik Peeters, Maarten Van Cauwenberghe, Jurgen Verheyen

Performers - tour (from September 2000): Annabelle Chambon, Cédric Charron, Anny Czupper, Els Deceukelier, Lisbeth Gruwez, Erna Omarsdottir, Frank Pay, Diederik Peeters, Dag Taeldeman, Maarten Van Cauwenberghe, Jurgen Verheyen

Music: composed by the musicians, plus: « Strange Fruit » written and composed by Lewis Allan 1940, Edward B. Marks Music Cy 3:30 « Killing in the name of » by Rage against the Machine Lyrics by Zack de la Rocha 1992, Retribution music (BMI) 5:13 « Sabotage » written by John Cale 1979, John Cale Music Inc. 4:25 « Le Chien » Paroles et musique de Leo Ferre 1984, RCA NL 70445 5:36

Tekst: Dario Fo: “io, Ulrike, grido” - additional texts written by the performers

Costume design: Daphne Kitschen Light design / technician: Sven Van Kuijk technician Kris Van Aert technical director / sound André Schneider production management Hilde Vanhoutte production Troubleyn/Jan Fabre (Antwerpen, België). coproduction deSingel (Antwerpen, België), Festival Montpellier Danse 2000, Théâtre de la Ville (Parijs, Frankrijk), Festival Theaterformen Expo 2000 (Hannover, Duitsland), Festival Bogotà 2000, Le-Maillon (Straatsburg, Frankrijk). avant-première 07.04.2000, Teatro Nacional, Bogotà première 14.06.2000 World Expo, Hannover